The Bouba-Kiki Effect and Task: Insights on its Role in Research

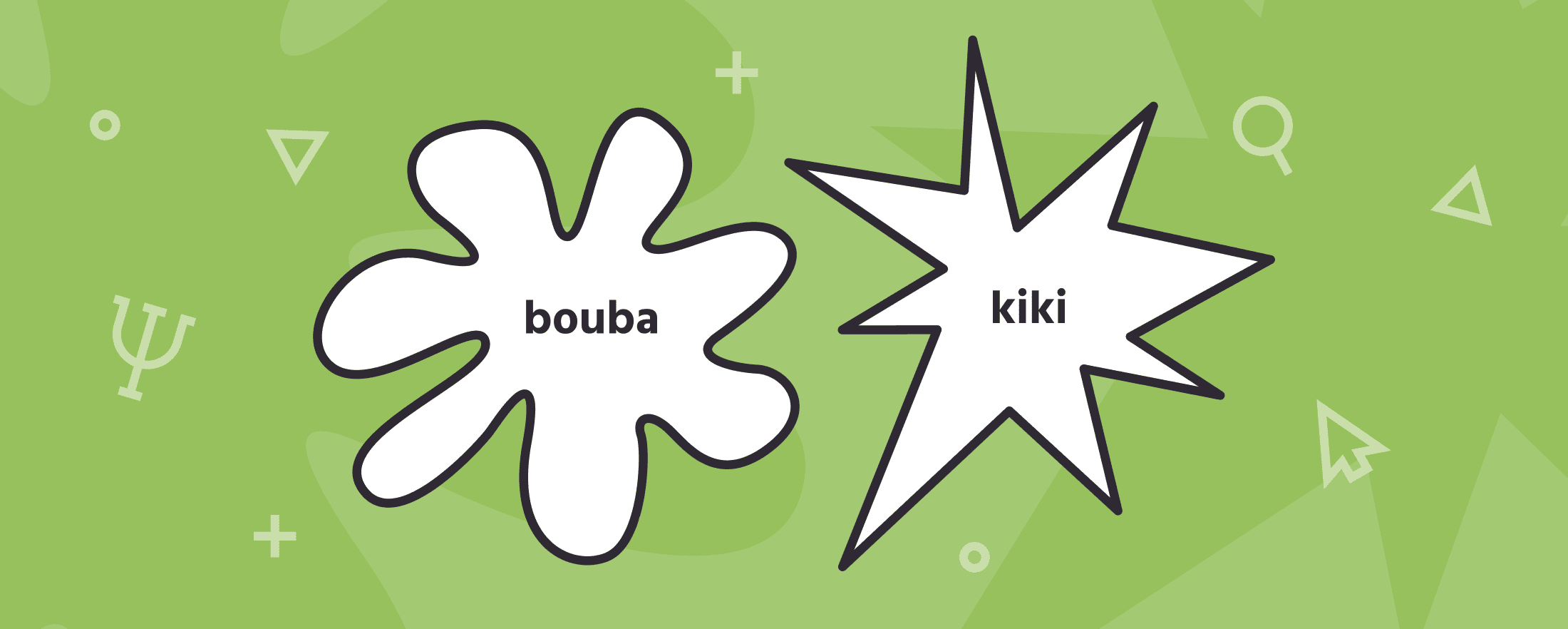

A fascinating concept that has been around since the 20th century and is still actively being used in different fields of study is the Bouba-Kiki Effect. The Bouba-Kiki effect is the systematic mapping between round/spiky shapes and speech sounds (“Bouba”/“Kiki”) (Piller, 2023). The Bouba-Kiki effect is a well-known synaesthesia where people are likely to assign specific, but nonsense words, like “Bouba” and "Kiki," to correspond with specific shapes—round and spiky, respectively.

History of the Bouba-Kiki Effect

The Bouba-Kiki effect dates back to the 1920s, with researchers citing Wolfgang Köhler’s written works and Dimitri Uznadze’s experiments as the main sources of where this effect was first observed and discussed.. The experiment in question is one where the participants were shown two shapes—a round and a spiky one. The participants were asked to match the words ‘takete' and 'malumba' to the shapes. Most participants matched the word 'malumba' to the round shape and ‘takete' to the spiky shape (Svantesson, 2017).

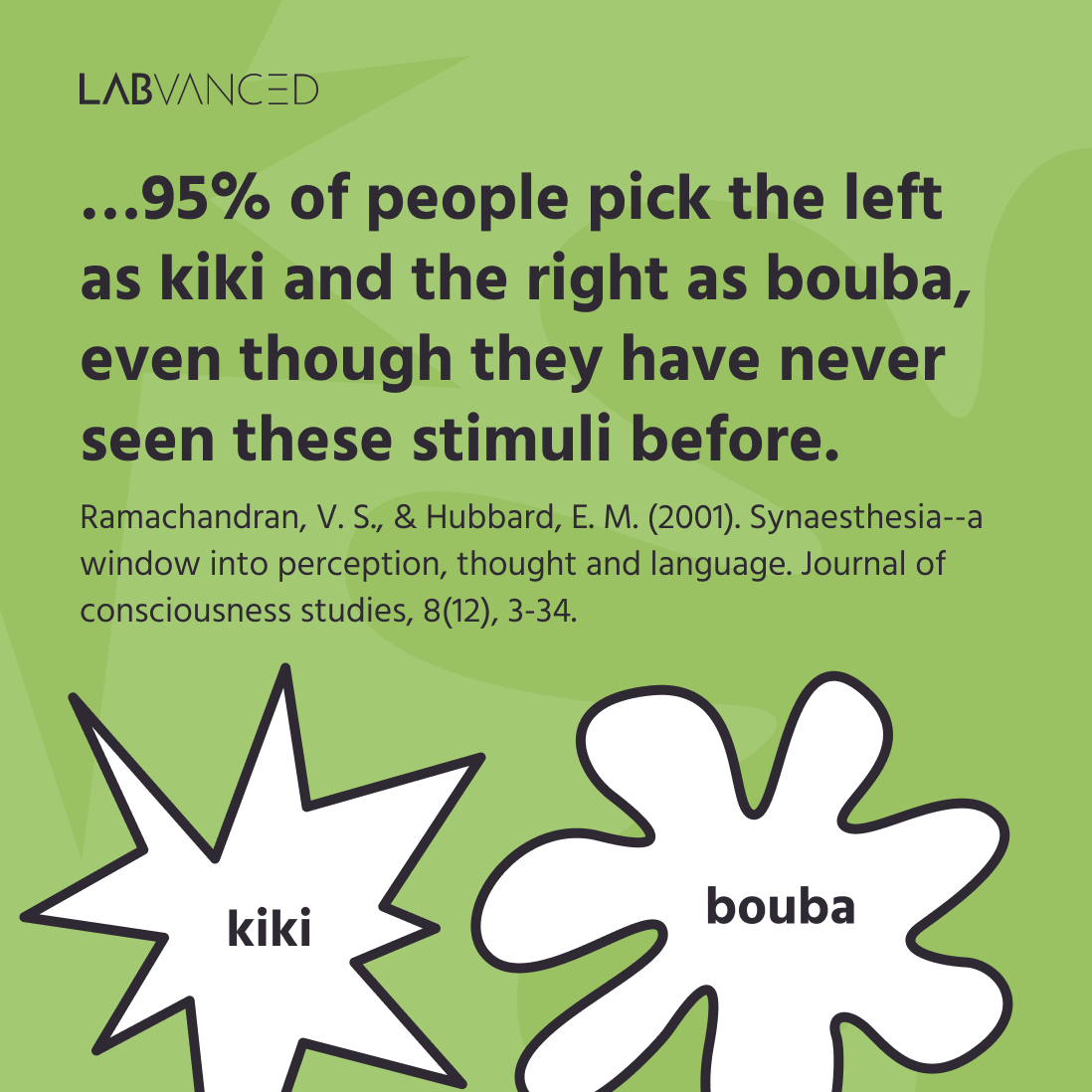

Although the core principle of association remains the same, through the years, novel approaches have been adopted by researchers to study the phenomenon further. The 2001 study by Ramachandran & Hubbard, is one such study that used the terms ‘kiki’ and ‘bouba’ in a similar setup. They suggested the existence of “a synaesthetic mapping between sound contour and motor lip and tongue movements,” implying that ‘kiki’ is named due to the sharp movements by mouth and ‘bouba’ because of the smooth, round shape by mouth when pronounced.

Today, researchers are still captivated in understanding this phenomenon and use dynamic combinations of stimuli categories like sound, shape, color, and even taste. These efforts ultimately help researchers gain a better understanding of how our sensory modalities interact and work together to process and make sense of different types of stimuli.

Cognitive Functions and Processes

While there are many cognitive functions that can be linked to the Bouba-Kiki task, here are a few that are commonly discussed:.

- Crossmodal correspondence: Crossmodal correspondence is the tendency for normal observers to match distinct dimensions of experience across different sensory modalities, (e.g., linking a sound with a shape) (Frontiers Research Topics, 2024).

- Sound symbolism: It is a non-arbitrary relationship between the meaning of a word and its sound (D’Anselmo et al., 2019).

- Synesthesia: Synesthesia is a fascinating neurological condition where ‘sensory overlap’ occurs. Basically, the stimulation of one sense or perceptual stream ‘crosses over’ and leads to a subjective experience of a different perceptual stream (Coulson, S., 2018). In popular culture, this may be known as ‘seeing colors.’

- Ideasthesia: Ideasthesia is related to synesthesia but occurs even when there is no direct impact or physical presence of the stimulus. In other words, ideasthesia occurs when the concept behind a sensory stimuli triggers a sensory response and not just the stimuli itself (Mroczko-WÄ et al., 2014).

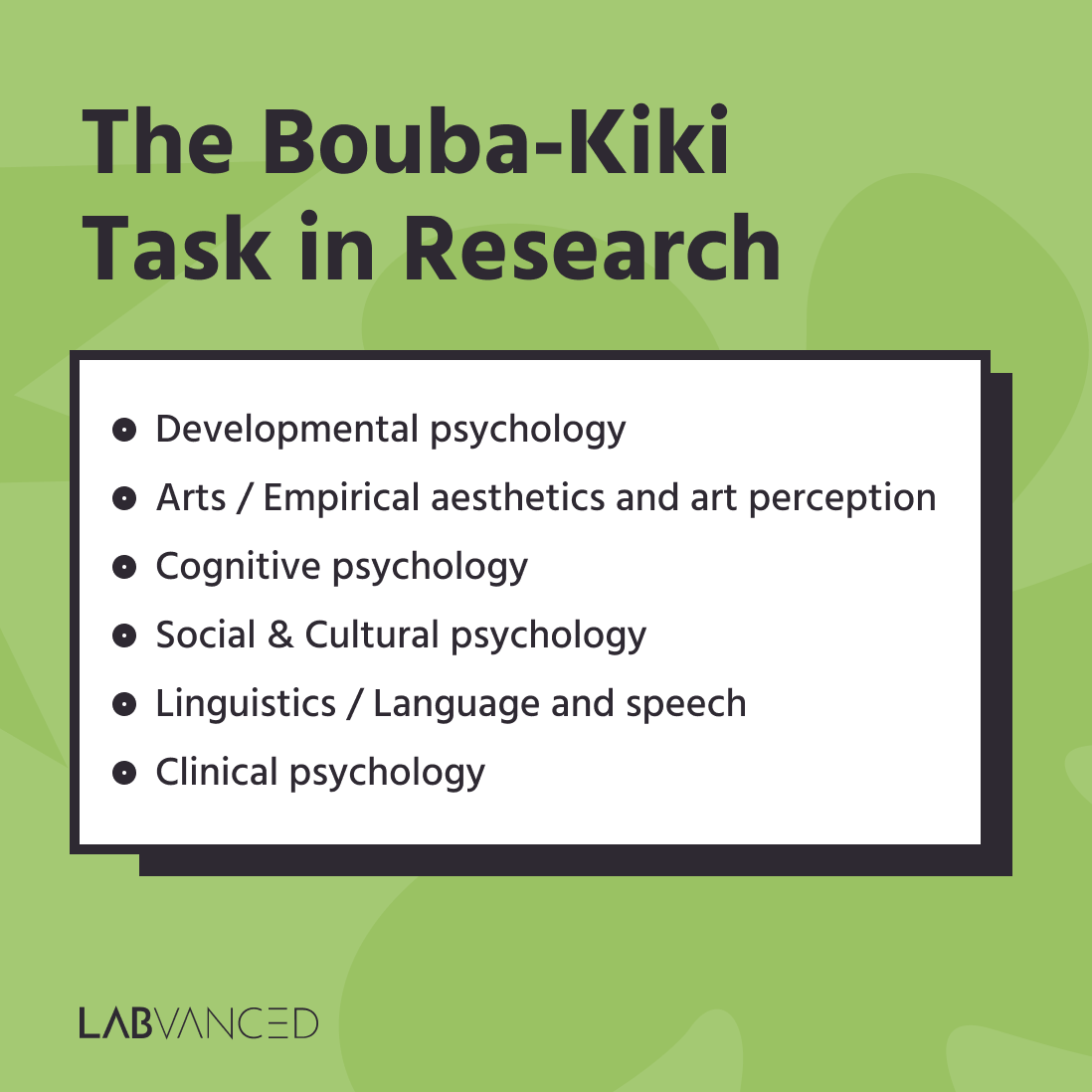

The Bouba-Kiki Effect in Research

The Bouba-Kiki effect has shown to be a great tool for studying sensory and perception interactions across several distinct research fields, shedding light on how humans associate and come to understand different categories of sensory stimuli. The implications of the Bouba-Kiki effect in research go beyond studying mere sensory associations, influencing areas such as developmental and cognitive psychology, but also research in the realm of linguistics and education. The Bouba-Kiki effect also serves as a means of understanding artistic expression and has even been used in the context of clinical psychology, as described further below.

Developmental Psychology

A study by Cullen et al. (2020) set out to use the Bouba-Kiki effect to see how children associate abstract shapes with phonetic sounds and whether this would impact their learning. As phonetics is concerned with connecting sounds with letters, the Bouba-Kiki effect came into play via the audio-visual route. The researchers wanted to see if using fun, hands-on tools could possibly help kids learn phonics. The results showed that when kids were presented with colorful models that they could touch and even smell, they made stronger connections between the sounds and the letters.

Art and Aesthetics Research

In the arts, the Bouba-Kiki effect holds a special role as there are lots of movements that are interested in the sensory overlap between how art forms are presented, such as combining music with visual representations. One such study set out to explore links between musical sounds (timbres) and shapes (Adeli et al., 2014). The researchers observed that harsh sounds, like cymbals, were often matched with sharp shapes. On the other hand, soft sounds, like piano notes, corresponded to rounded shapes. Mixed sounds, which had both soft and harsh qualities, were linked to shapes combining round and sharp elements, highlighting how we instinctively match sounds to visuals across sensory experiences.

In a different study, the Bouba-kiki effect was studied within the context of contemporary art by presenting art pieces (visual and music) that were either corresponding (ie. intended) in their nature or random.

Example of a contemporary artwork used to study congruency between visual stimuli and sounds (Fink, L., Fiehn, H., & Wald-Fuhrmann, M., 2024).

The online experiment consisted of 4 conditions: Audio, Visual, Audio-Visual-Intended (artist-intended pairing of art/music), and Audio-Visual-Random (random shuffling). Participants (N=201) were presented with 16 pieces and could click to proceed to the next piece whenever they liked. After each piece, they were asked about their subjective experience. Available here: https://www.labvanced.com/player.html?id=33023 The Audiovisual-Intended pieces (ie. the pieces where the music composition was created for the specific artwork) were perceived to have greater correspondence than those in the Audiovisual-Random condition (Fink, L., Fiehn, H., & Wald-Fuhrmann, M., 2024).

Cognitive Psychology

The study by Ogata et al. (2023) employed the Bouba-Kiki effect to examine how the shape of food influences taste perception. The goal was to explore how Bouba-shaped (rounded) and Kiki-shaped (angular) chocolate pieces affect participants' sweetness ratings. The findings indicated that participants perceived the Bouba-shaped chocolates as significantly sweeter than the Kiki-shaped ones!

Social & Cultural Psychology

Ćwiek et al. in 2021 examined the bouba/kiki effect to understand how people from different cultures associate sounds with shapes to investigate whether it is consistent across various cultures and writing systems. An online survey was conducted by the researchers on participants from 25 different countries which led to the finding that individuals, irrespective of their country of origin, tend to associate the word "bouba" with round shapes and "kiki" with spiky shapes. This further implies that the Bouba- kiki effect is universal, independent of cultural or linguistic influences.

Linguistics

A study by Kasap et al. (2024) explored how students connect sounds with shapes using the bouba-kiki effect. The participants were presented with two abstract shapes and were asked to connect those with the pseudowords "bouba" and "kiki." It was found that a significant majority (87.2%) connected round shaped figures with “bouba’ and spiky figures with “kiki.” This study highlights the underlying cognitive processes of language perception.

Clinical Psychology

The Bouba-Kiki effect can be applied to clinical psychology for gaining a better understanding of conditions in which language, for example, is impacted.

The Bouba-Kiki effect was utilized by Gold et al. (2022) in a study to investigate how children diagnosed with speech disorders make associations between different sounds and visual shapes. The study specifically focused on children with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) to explore how these children associate sounds with shapes. The researchers compared the performance of children with CAS with a group of children with developmental language disorders (DLD) and typically developing (TD) children. The findings revealed that children with CAS struggled more, as compared to other groups, to make these associations suggesting that their ability to integrate information from different sensory modalities may be impaired, which could be a contributing factor to their speech difficulties.

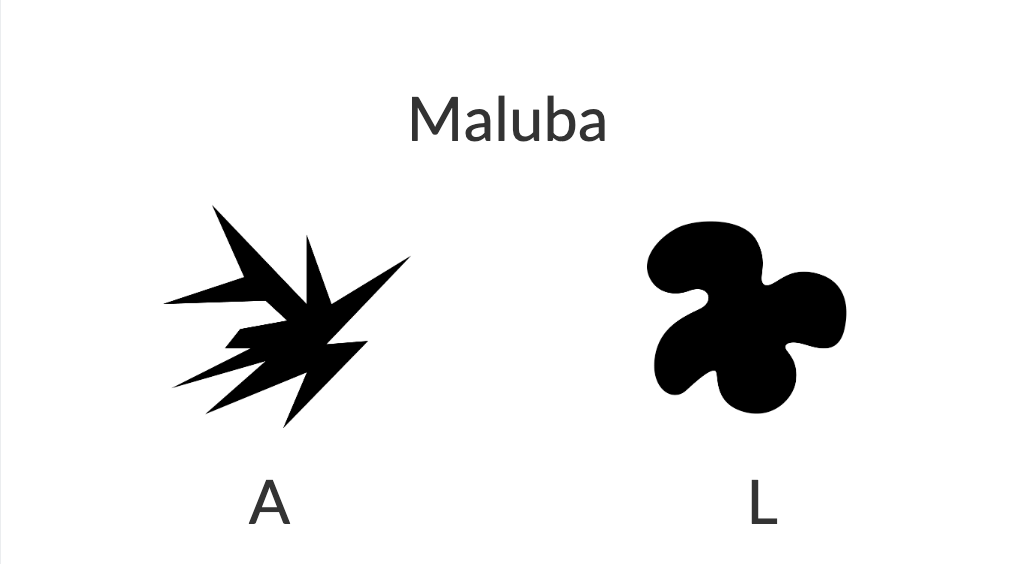

H2: Designing the Bouba-Kiki Task: Example

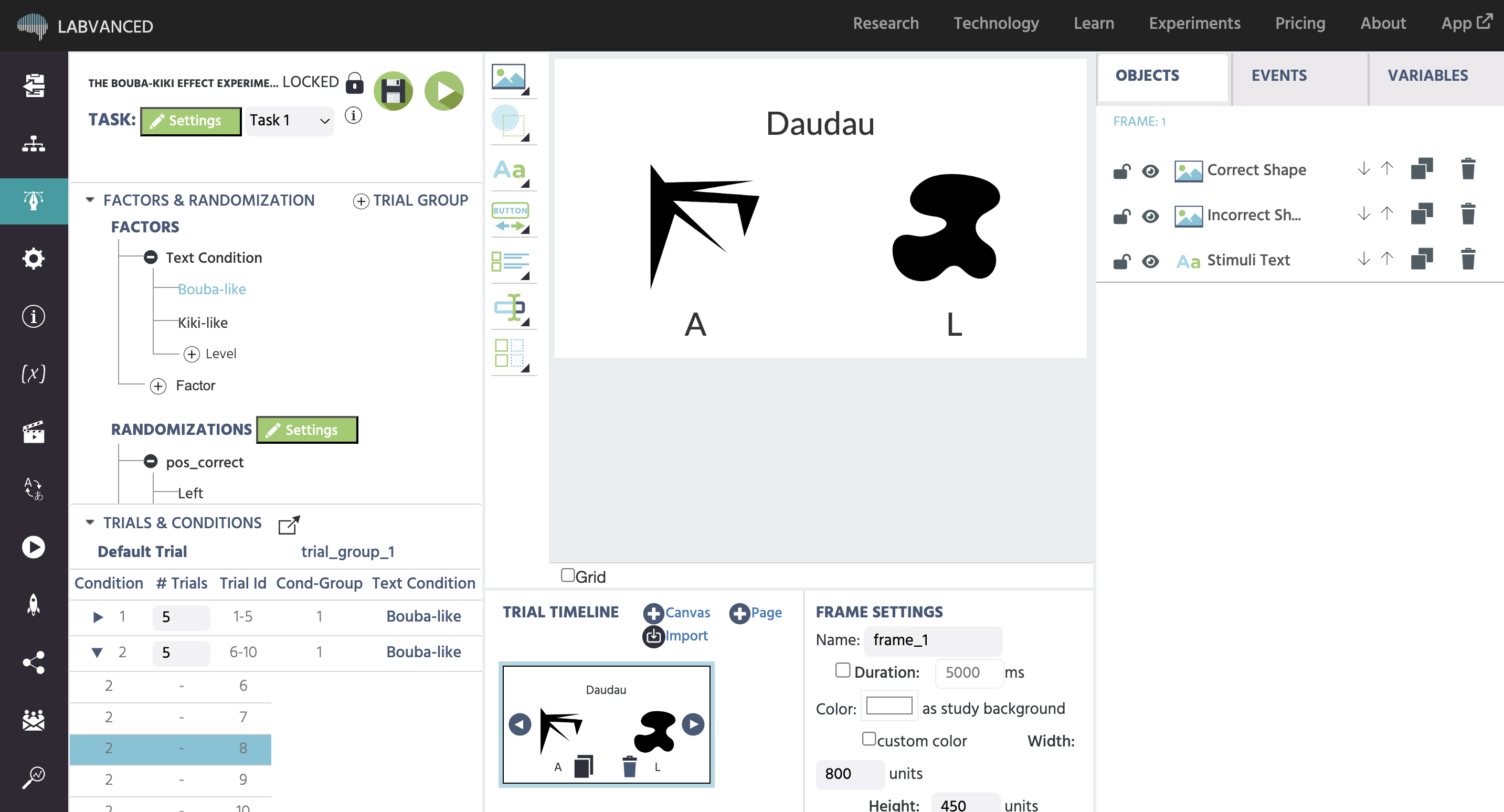

In this sample task, the participants are presented with a word alongside two images per trial. The shapes presented are either round or spiky-shaped. The participant is asked to indicate the shape that best corresponds with the presented word by pressing the keyboard letter A to select the left-side shape or L for the right-side shape.

The image below is an example of how a trial would look like in Labvanced:

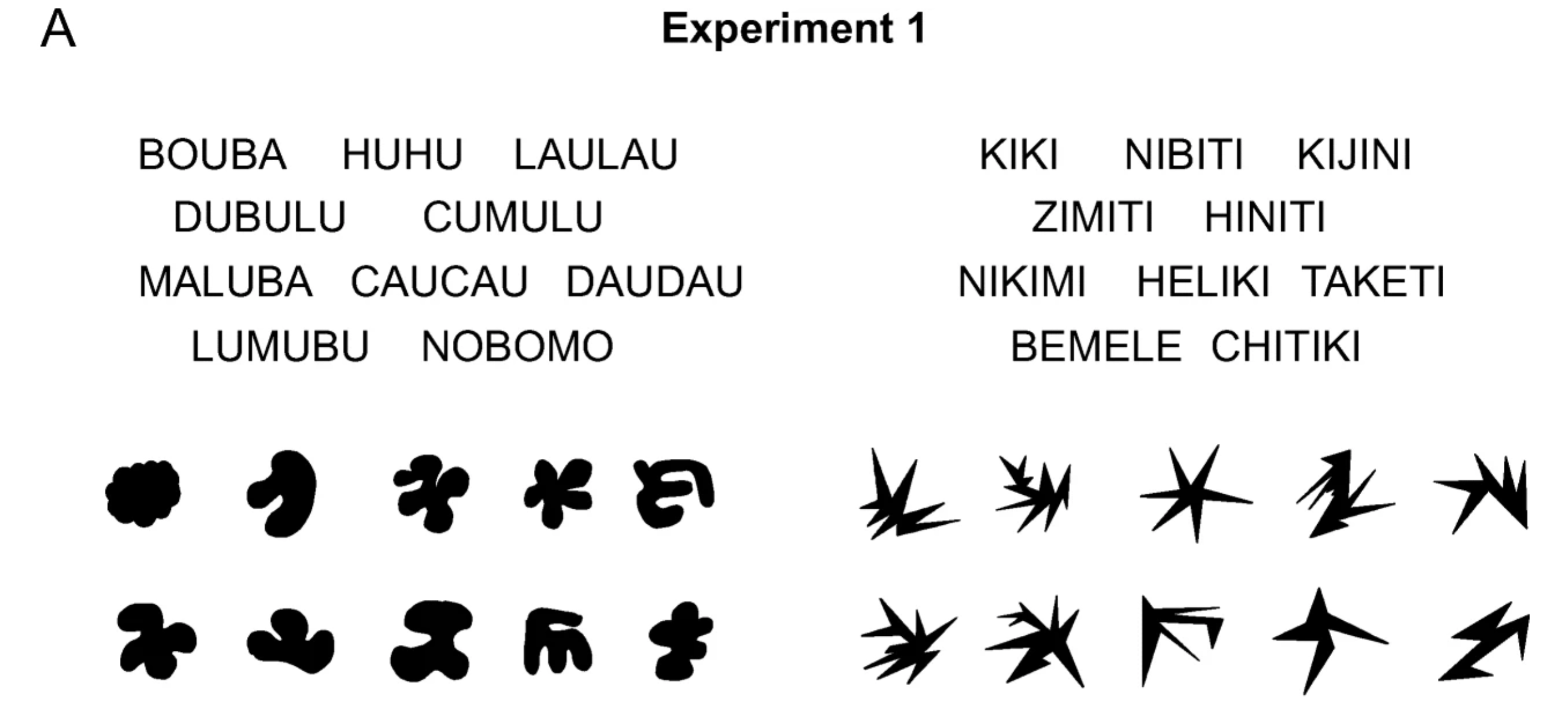

Experimental Stimuli: Bouba Kiki Shapes and Text

The stimuli used for the study involve:

- Non-words/non-sense words: These words are sequences of letters that do not form actual words in any language but are constructed to resemble real words.

- Abstract visual stimuli as shapes: These shapes do not correspond to any real object but help analyze perceptual associations based purely on form.

The stimuli used this task are shown below:

Image from the research paper ‘The Bouba–Kiki effect is predicted by sound properties but not speech properties’ (Passi, A., & Arun, S. P. ,2024)

The image below is an example of designing a Bouba-Kiki task in Labvanced. The task used images as factors, customized the required number of trials, and further randomized them as per the study requirements.

By offering a range of dynamic stimuli options such as images, videos, audio, text, etc., Labvanced enables us to design engaging experiments that cater to diverse research needs. Additionally, it allows us to customize the number of trials required, as well as scientifically randomize and balance the stimuli, ensuring a controlled experimental design.

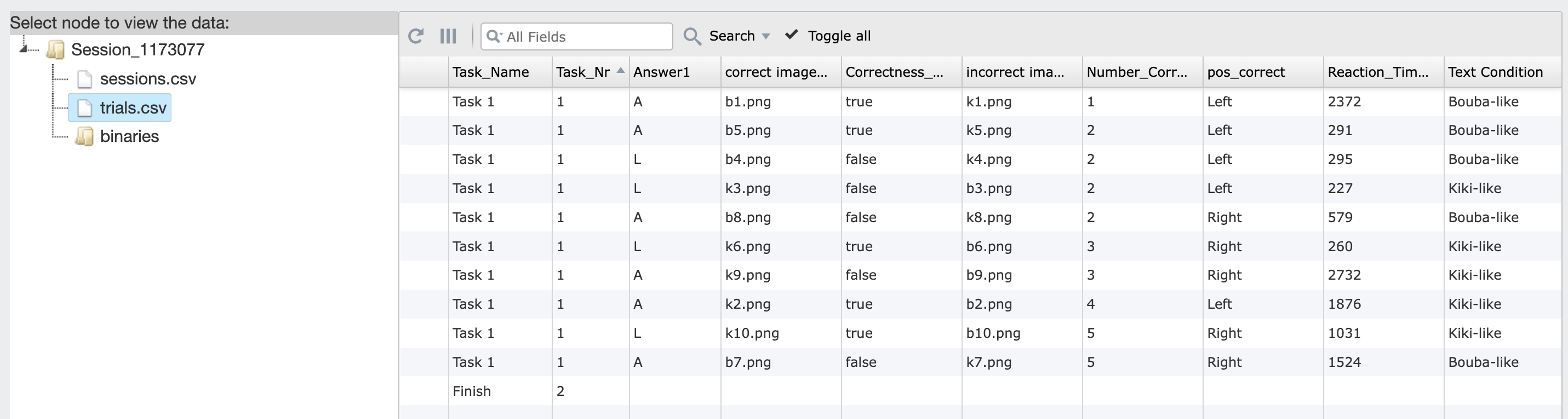

Measurement & Data

The data recorded from the Bouba-Kiki task include:

- Answer / Choice of Participants: The key value indicating the image / shape that the participant selected in the trial.

- Correct image file name: The name of the image that was presented and is the ‘correct’ image.

- Incorrect image file name: The name of the image that was presented and is the ‘incorrect’ image.

- Correctness response: Whether the answer the participant selected is correct or not.

- Number of correct answers: The running total of the correct responses.

- Reaction Time: The time taken by the participant to select their answer in milliseconds.

The image below shows the Dataview & Export page in Labvanced with the recorded data:

Possible Confounds to Consider

When using the Bouba-Kiki effect in research, it’s important (just as with any experiment) to keep in mind potential confounds that could influence the observed results. The following confounding variables may need to be accounted for in your research as they may possibly influence how participants perform in tasks relating to the Bouba-Kiki effect:

- Culture: The Bouba-Kiki effect has been observed to vary between Western and Eastern cultures (Chen et al., 2016). These cross-cultural differences have also been noted in the context of basic tastes and visual features (Wan et al., 2014).

- Age: It was observed that young children exhibited inconsistent audio-tactile (AT) associations, while adults demonstrated the expected associations in a study by Chow et al., in 2021.

- Orthography: Participants speaking languages with Roman scripts were only marginally more likely to show the Bouba-Kiki effect (Ćwiek et al., 2021), hinting at the possible orthographic influence.

Variations of the Bouba-Kiki task

As the Bouba-Kiki effect is a phenomenon, there are several ways that it can be harnessed in research. The following variations of the Bouba-Kiki task have been explored in the literature:

- Real Lexical Stimuli and Character Silhouettes Associations: The task explored and found an association between roundness/sharpness of the phonemes in first names and round or sharp shapes in the form of character silhouettes (Sidhu et al., 2015).

- Timbre and Visual Shape Associations: As mentioned previously, a relationship between sound and shape has been consistently observed in the literature. When, musical sounds were presented with varying timbres and were presented with visual shapes of different colors, an effect of color was also found. While soft timbres were strongly associated with blue, green, or light gray rounded shapes, harsh timbres were linked to red, yellow, or dark gray sharp angular shapes (Adeli et al., 2014).

- Phonemes and Personality Traits: Adjectives previously judged to be either descriptive of a figuratively ‘round’ or a ‘sharp’ personality were associated with names containing either round- or sharp-sounding phonemes, respectively (Sidhu et al., 2015).

- Taste Hedonics-Shape Associations: The task explored the association between taste quality, intensity, and liking and the roundness/angularity of the tastants. There was a positive correlation between perceived intensity and roundness/angularity, except for sweet tastes, and a negative correlation between liking and roundness/angularity for all tastes (Velasco et al,. 2016).

- Gender and Visual Shape Associations: The task explored the association between shape characteristics and gender. The researchers showed that round shapes were linked with female names, and sharp shapes were associated with male names (Sidhu et al., 2015).

- Audio-visual Correspondence and Aesthetic Experience Associations: In this experiment, the researchers used Labvanced to explore the relationship between audio-visual modalities and congruency and its impact on aesthetic experience. Most participants reported feeling more moved by the congruent audio-visual conditions compared to just audio or visual conditions alone (Fink, L., Fiehn, H., & Wald-Fuhrmann, M., 2024).

References

- Adeli, M., Rouat, J., & Molotchnikoff, S. (2014). Audiovisual correspondence between musical timbre and visual shapes. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00352

- Chen, Y.C., Huang, P.C., Woods, A., & Spence, C. (2016). When “Bouba” equals “kiki”: Cultural commonalities and cultural differences in sound-shape correspondences. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26681

- Chow, H. M., Harris, D. A., Eid, S., & Ciaramitaro, V. M. (2021). The feeling of “Kiki”: Comparing developmental changes in sound–shape correspondence for audio–visual and audio–tactile stimuli. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 209, 105167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105167

- Coulson, S. (2018). Metaphor and synesthesia. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 135–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.plm.2018.09.003 Crossmodal correspondence. (2024). Frontiers Research Topics. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-8325-4701-4

- Cullen, C., & Metatla, O. (2020). Tangible multisensory AIDS for Collaborative Phonics Learning. Companion Publication of the 2020 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1145/3406865.3418342

- D’Anselmo, A., Prete, G., Zdybek, P., Tommasi, L., & Brancucci, A. (2019). Guessing meaning from word sounds of unfamiliar languages: A cross-cultural sound symbolism study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00593

- Fink, L., Fiehn, H., & Wald-Fuhrmann, M. (2024). The role of audiovisual congruence in aesthetic appreciation of contemporary music and visual art. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 20923.

- Gold, R., Klein, D., & Segal, O. (2022). The Bouba-Kiki effect in children with childhood apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_jslhr-21-00070

- Kasap, S., & Ünsal, F. (2024). A psycholinguistic study of the Bouba-Kiki Phenomenon: Exploring associations between sounds and shapes. East European Journal of Psycholinguistics, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.29038/eejpl.2024.11.1.kas

- Mroczko-Wąsowicz, A., & Nikolić, D. (2014). Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, 509.

- Nielsen, A., & Rendall, D. (2011). The sound of round: Evaluating the sound-symbolic role of consonants in the classic takete-maluma phenomenon. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale, 65(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022268

- Ogata, K., Gakumi, R., Hashimoto, A., Ushiku, Y., & Yoshida, S. (2023). The influence of bouba- and kiki-like shape on perceived taste of chocolate pieces. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1170674

- Passi, A., & Arun, S. P. (2024). The Bouba–Kiki effect is predicted by sound properties but not speech properties. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 86(3), 976-990.

- Piller, S., Senna, I., & Ernst, M. O. (2023). Visual experience shapes the Bouba-Kiki effect and the size-weight illusion upon sight restoration from congenital blindness. Scientific Reports, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38486-y

- Ramachandran, V. S., & Hubbard, E. M. (2001). Synaesthesia--a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(12), 3–34.

- Shukla, A. (2016). The Kiki-Bouba Paradigm : Where senses meet and greet. Indian Journal of Mental Health(IJMH), 3(3), 240. https://doi.org/10.30877/ijmh.3.3.2016.240-252

- Sidhu, D. M., & Pexman, P. M. (2015). What’s in a name? sound symbolism and gender in first names. PLOS ONE, 10(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126809

- Svantesson, J. (2017). Sound symbolism: The role of word sound in meaning. WIREs Cognitive Science, 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1441

- Velasco, C., Woods, A., Liu, J., & Spence, C. (2016). Assessing the role of taste intensity and hedonics in taste–shape correspondences. Multisensory Research, 29(1–3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134808-00002489

- Wan, X., Woods, A. T., van den Bosch, J. J., McKenzie, K. J., Velasco, C., & Spence, C. (2014). Cross-cultural differences in crossmodal correspondences between basic tastes and visual features. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01365

- Ćwiek, A., Fuchs, S., Draxler, C., Asu, E. L., Dediu, D., Hiovain, K., Kawahara, S., Koutalidis, S., Krifka, M., Lippus, P., Lupyan, G., Oh, G. E., Paul, J., Petrone, C., Ridouane, R., Reiter, S., Schümchen, N., Szalontai, Á., Ünal-Logacev, Ö., … Winter, B. (2021). The bouba/kiki effect is robust across cultures and writing systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1841). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0390