The Mental Rotation Task

The Mental Rotation Test is a powerful task in the field of cognitive psychology for studying spatial processing. Read on to learn more about the details of the 2D and 3D mental rotation task, its history, how it can be conducted (including in an online setting), the powerful research findings that it can unveil, as well as examples of experiments that have made use of this task!

History of the Mental Rotation Task

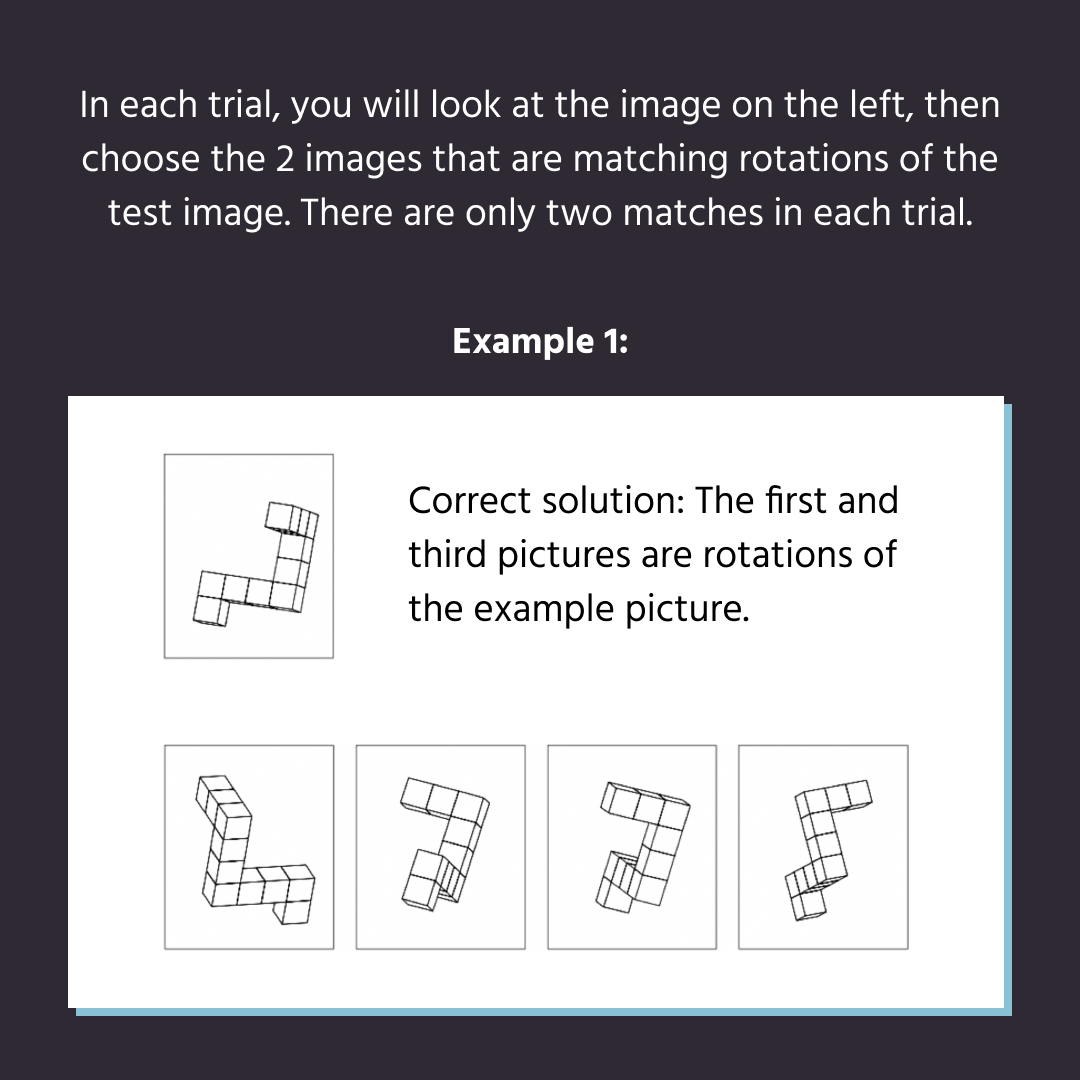

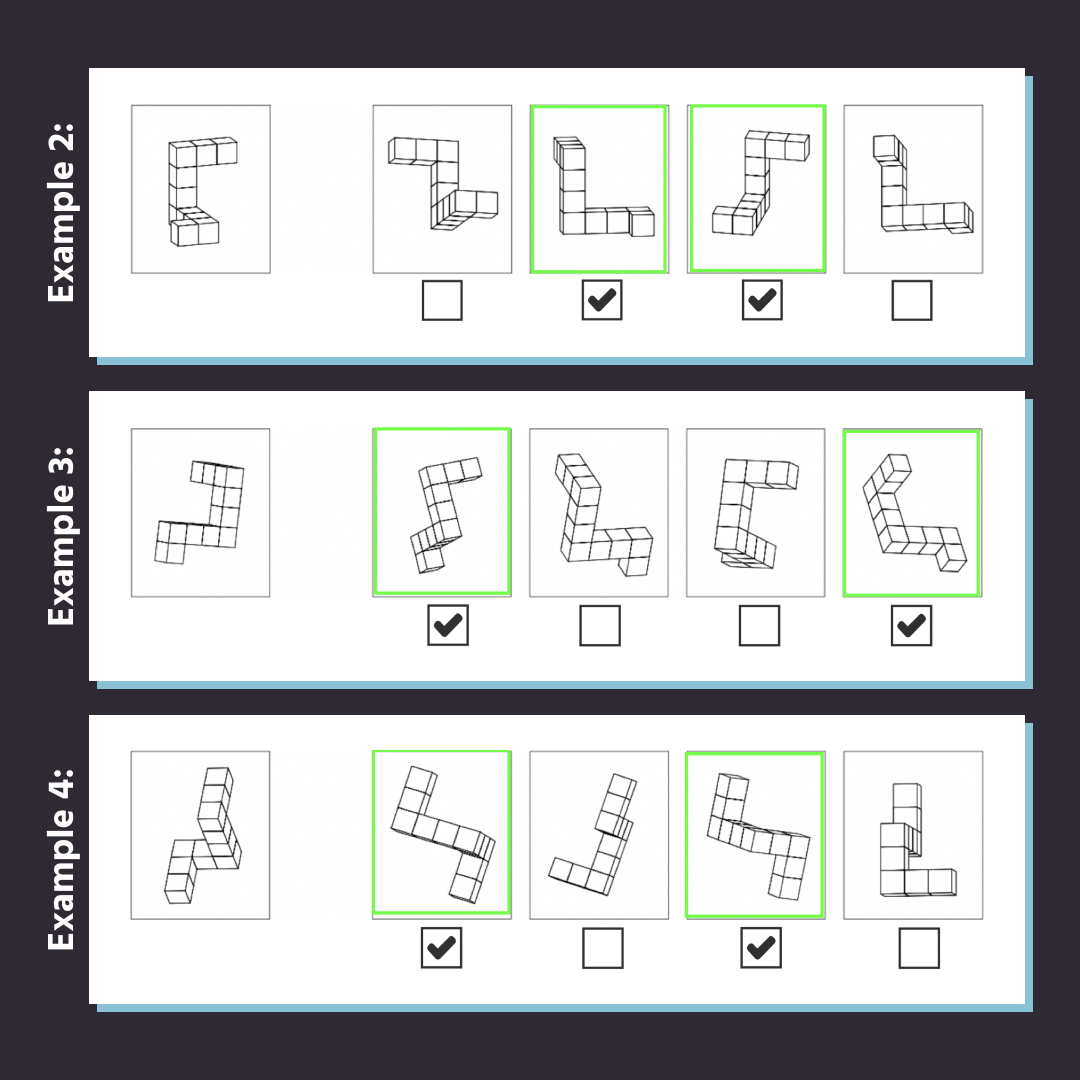

The mental rotation test dates back to the 1970s when it was developed to study one’s abilities to mentally rotate objects. In 1971, Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler were among the first to objectively study mental rotation by presenting several pairs of 3D, cubed, or asymmetrically lined objects and subsequently measuring reaction time when participants were determining whether the paired objects were a match (Shepard, R. N., & Metzler, J., 1971). In 1978, Steven G. Vandenberg and Allan R. Kuse formalized the Mental Rotations Test based on the 1971 Shepard and Metzler mental rotation task by presenting 3D objects at different orientations by rotating it around a vertical axis. This was a 20-item test and the participant had to compare four figures and select two choices that matched the criterion figure (Vandenberg, S. G., & Kuse, A. R., 1978).

About the Mental Rotation Test

What does the mental rotation task require of participants? It’s quite straightforward actually!

The general overview of the mental rotation experiment is as follows:

- The participant is presented with a criterion / target object

- The participant must decide which two options (from the four presented) are a match to the criterion / target object

Thus, the participants must examine the referrent stimuli and choose which stimuli are matching rotations. In the image above, the referrent stimuli matches with the first and third stimuli. Below, are additional examples of what trials in the 3D mental rotation task look like:

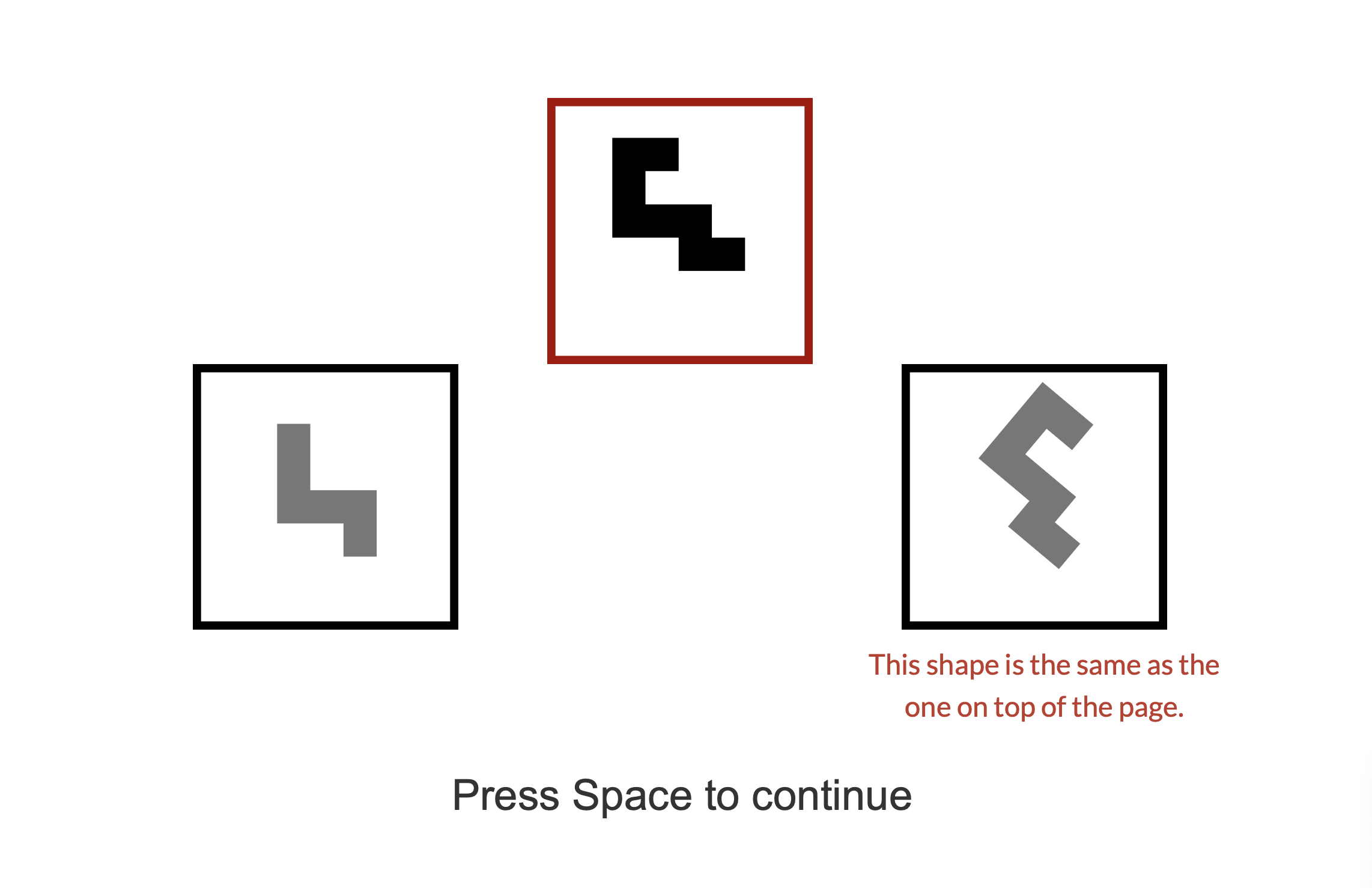

2D Rotation

In some versions of the mental rotation experiment, 2D shape rotation is tested:

Administering the 2D or 3D Mental Rotation Test

The mental rotation task in Labvanced can be performed by:

- Administering the test online (for remote studies) for which the URL study link can easily be shared with participants, or

- Locally without an internet connection using our desktop app

- Researchers can import the task to their design editor and set up the experiment without having to code. Check out the mental rotation tests in Labvanced here, simply click the ‘participate’ button to try it or ‘import’ to upload it to your account to use it as the basis of your experiment:

- Furthermore, advanced features like our webcam-based eye tracking can also be included in order to add an extra layer of physiological data, in addition to reaction times.

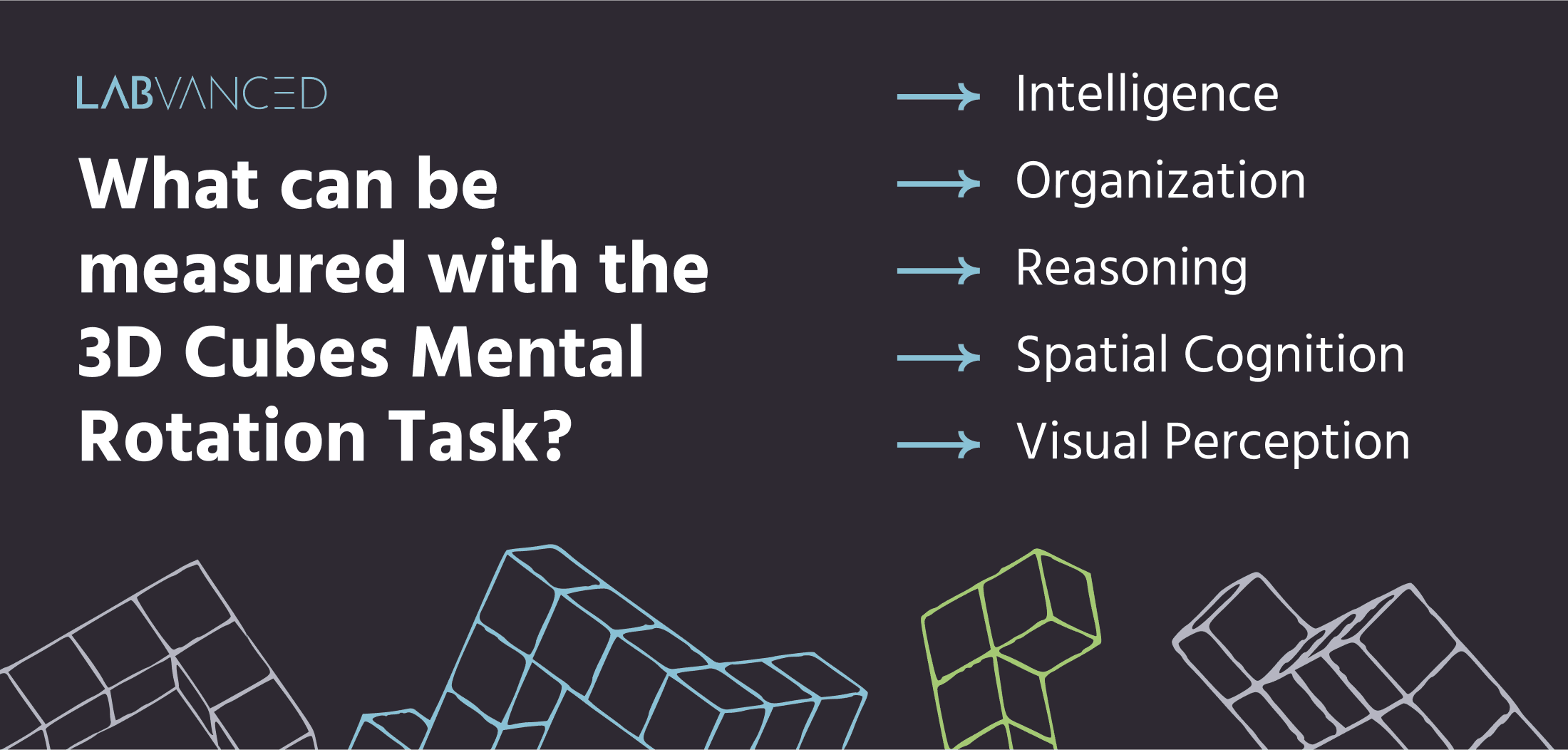

Cognitive Functions and Processes

Several cognitive functions and processes are uncovered by mental rotation experiments, including:

- Intelligence

- Organization

- Reasoning

- Spatial Cognition

- Visual Perception

When matching two images that are identical, the following cognitive processes are implicated in the mental rotation test:

- Perceptual preprocessing

- Identification / discrimination of the stimuli

- Identification of the stimuli’s spatial orientation

- Judgment of the parity

- Behavioral response, ie: choice selection / execution

Together, these processes allow a participant to successfully complete a mental rotation task (Kaltner, S., & Jansen, P., 2014).

Measurement and Data from the Mental Rotation Test

- Accuracy / Error rate: the overall accuracy or errors performed throughout the task.

- Angular disparity: refers to the particular angle that the stimulus has with respect to the referrent stimulus.

- Nondecision time: the amount of time that other processes take beyond decision making, such as stimulus encoding and the execution of motor responses.

- Drift rate: the time which its takes to accumulate information.

- Boundary separation: the distance between two separate responses. This value becomes wider when accuracy is prioritized over speed, as well as when the rotation angle is increased.

- Reaction time: the time it takes to select a response.

- Gaze duration / fixations: if eye tracking is employed, then relevant metrics like gaze duration and fixations can also be reported as a means of understanding the participants’ visual processing strategy. An example of results reported utilizing eye tracking data in the context of the mental rotation task includes the run count ratio (RC ratio) which is calculated by dividing the mean number of fixations in incorrect answers by that in correct answers (Suzuki et al., 2018).

Possible Confounds to Consider

Certain confounds ought to be considered during the experimental design and data analysis stages, such us:

- Sex differences: For 2D and 3D mental rotation tasks, males have a cognitive advantage (Collins, D. W., & Kimura, D., 1997). This finding has been supported by a metasynthesis study with a sample of over 12 million participants concluding that, when it comes to the mental rotation test, males show the largest cognitive sex difference in psychological literature (Zell, E., Krizan, Z., & Teeter, S. R., 2015).

- Spatial anxiety / self-confidence: Related to the point above, a different study found that the pronounced sex/gender differences in the mental rotation task may be mediated by spatial anxiety and self-confidence, especially when task demands are high (Arrighi, L., & Hausmann, M. , 2022).

- Handedness: While not as striking as the confound of sex, handedness also plays a role in mental rotation performance. It has been shown that right-handers are faster than left-handers. Also handedness plays a role in facilitation when images presented correspond to the dominant hand (Jones et al., 2021).

MRT Scores Uses

As study goals can vary, below are the most common uses of the scores obtained from the mental rotation tests:

- Description of the participants’ spatial skills: to quantify an aspect of spatial skills and reasoning.

- Comparison of cognition within groups: to quantify and compare the cognitive processes related to MRT between two groups, such as dyslexic participants versus controls.

- Treatment outcome: where the main focus is the effect of treatment and intervention, the MRT can be used as a measure to quantify specific changes related to spatial cognitive processing.

Variations of the Mental Rotation Test

The mental rotation task is typically with the classic cubes or 2D shapes, however there are some variations that appear in research that are worth mentioning:

- Different visual stimuli: Instead of cubes, it’s also common to see other types of visual stimuli presented and rotated in mental rotation experiments, such as: letters, animals, faces, colored shapes, and pseudo-letters (shapes that look like letters but are not) (Kaltner, S., & Jansen, P., 2014).

- cMRT: In chronometric studies of mental rotation (cMRT), two stimuli are presented (instead of 4) with differences in the angular disparity. The participant has to quickly decide whether the two presented images are the same or not. (Titze, C., Heil, M., & Jansen, P., 2008)

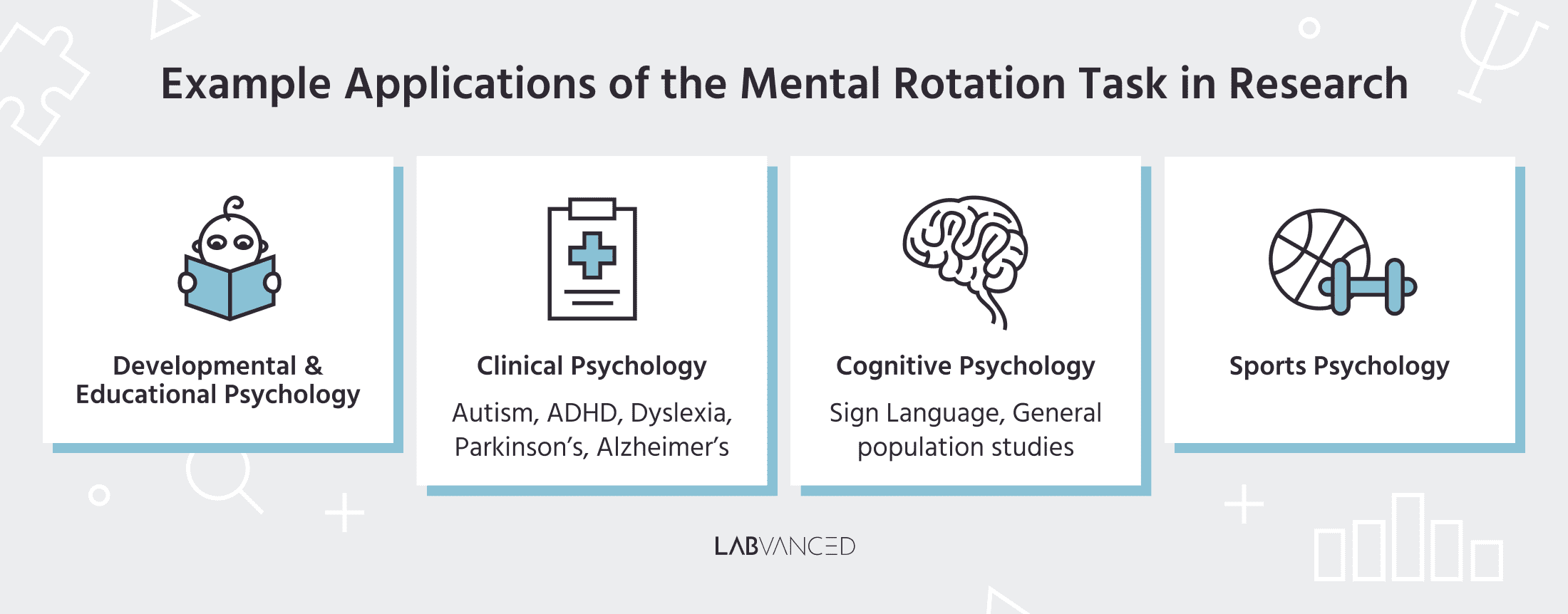

Mental Rotation Test Examples: Applications & Experiments

The mental rotation tasks are popular in psychology research as they are easy to implement yet reveal a lot about spatial skills and abilities. Below are some examples of applications and experiments.

Developmental & Educational Psychology

- Development of spatial abilities: Mental rotation tasks are administered in developmental psychology experiments in order to understand how spatial cognition skills evolve with age. An example of this is a study that compared performance on the mental rotation task between 3-year-olds, 4-year-olds, and five-year-olds and showed that 3-year-olds can begin to perform this task above chance level (Krüger, M., 2018).

- Mental Rotation improving mathematical performance: A different study showed how a 1-week online training intervention with mental rotation spatial training for 6- and 7-year olds transfers to canonical arithmetic problems. This group, compared to a control group that received literacy training, showed improved performance on certain arithmetic problems which might be due to improving visualization ability and/or increasing the capacity of visuospatial working memory (Cheung, C.N., Sung, J.Y., & Lourenco, S.F., 2019).

Clinical Psychology

- Autism: A certain subgroup of autistics has been found to possess enhanced visuospatial abilities. This has been supported through cognitive tests that include mental rotation tasks where this group performs faster. The cognitive advantage is particularly defined for 3D shapes of high complexity, as opposed to simple or 2D stimuli. Current research trends are exploring neural correlates of such performance and have found greater occipital and parietal functioning in autistics who have such visuospatial strengths (Thérien, V.D., et al., 2022).

- ADHD: Diffusion models have been developed to use values such as drift rate, nondecision time, and boundary separation to better understand cognition of ADHD participants in tasks such as the mental rotation test. Such experiments have shown that the poor performance of ADHD participants in the mental rotation experiment are due to a slow rate of evidence of accumulation and due to the relative inflexibility for boundary separation adjustment (Feldman, J. S., & Huang-Pollock, C., 2021).

- Dyslexia: Mental rotation tests, including 2D rotation and 2D shape rotation, are often administered to patients with dyslexia. As per the functional coordination deficit (FCD) model, dyslexics cannot decide is letters are mirrored or not due to the failure of suppressing symmetry when graphemic material is presented, thus cannot decide if a letter is mirrored or not due to the ambiguous mapping between grapheme and phoneme representations. Thus, due to the nature of the task, mental rotations which have to do with mirroring and rotation are relevant tests which can be administered to dyslexics. Compared to controls / normal readers, dyslexic children demonstrate a greater mental rotation effect given their slower reaction times. (Kaltner, S., & Jansen, P., 2014).

- Parkinson's Disease: Parkinson’s is a neurodegenerative disorder where both motor and cognitive skills decline through disease progression. These patients have been found to have decreased performance on the mental rotation task. Recent efforts have been made to utilize the mental rotation task as a cognitive biomarker tool for early-onset Parkinson’s disease without evidence of a mild cognitive deficit (Razzaque et al., 2024).

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Alzheimer’s patients demonstrate longer reaction times and lower accuracy in mental rotation tasks compared to healthy elderly adults. Researchers have also shown that the mental rotation task, combined with eye tracking can be utilized as a screening tool for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Suzuki et al., 2018).

Using the MRT in clinical psychology is not limited to just the above. It has been used to study spatial abilities in a wide range of clinical populations, such as patients with TBI or Huntington’s disease.

Cognitive Psychology

- General population studies: The mental rotation task has been used across many different types of studies that have cognitive psychology at its core. These experiments are conducted with healthy, neurotypical participants in order to understand spatial cognitive abilities. One such study, conducted in Labvanced, utilized the mental rotation task (in conjunction with other tasks) in order to assess the influence of spatial ability on time representation. The findings showed that higher spatial ability and chronological learning lead to better memory (Otenen, E., & Kanero, J., 2022).

- Sign language: A fascinating topic, as language and cognition dynamically overlap, for mental rotation tasks lies within the context of studying sign language. One such study demonstrated that there is a positive relationship between sign language users and mental rotation abilities (Kubicek, E., & Quandt, L.C., 2020).

Sports Psychology

The field of sports and exercise research is increasingly using the mental rotation task in the last few years and has reached many fascinating conclusions as motor coordination has the potential to influence performance.

- Basketball players with novel MRT task: In a recent study, novice and expert basketball players were administered a novel mental rotation test. Instead of the classic 3D cubes as stimuli, the participants saw six different basketball plays that were rotated or mirrored. The results were such that there was an effect of sex and an effect of expertise. Male participants solved more items and the performance was better for more expert players. This study paves the way for support-specific stimulus material (Weigelt, M. & Memmert, D., 2020).

Conclusion

The mental rotation task has a lot of foothold in research and is used by psychologists across various fields. The mental rotation task can be administered online or in-person and is commonly used to assess spatial cognition. There are many variations of the mental rotation task, but most experiments use 3D or 2D cube stimuli.

References

Arrighi, L., & Hausmann, M. (2022). Spatial anxiety and self-confidence mediate sex/gender differences in mental rotation. Learning & Memory, 29(9), 312-320.

Cheung, C. N., Sung, J. Y., & Lourenco, S. F. (2020). Does training mental rotation transfer to gains in mathematical competence? Assessment of an at-home visuospatial intervention. Psychological Research, 84(7), 2000-2017.

Collins, D. W., & Kimura, D. (1997). A large sex difference on a two-dimensional mental rotation task. Behavioral neuroscience, 111(4), 845.

Feldman, J. S., & Huang-Pollock, C. (2021). A new spin on spatial cognition in ADHD: A diffusion model decomposition of mental rotation. Journal of the international neuropsychological society, 27(5), 472-483.

Jones, H. G., Braithwaite, F. A., Edwards, L. M., Causby, R. S., Conson, M., & Stanton, T. R. (2021). The effect of handedness on mental rotation of hands: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Research, 85, 2829-2881.

Kaltner, S., & Jansen, P. (2014). Mental rotation and motor performance in children with developmental dyslexia. Research in developmental disabilities, 35(3), 741-754.

Kubicek, E., & Quandt, L. C. (2021). A positive relationship between sign language comprehension and mental rotation abilities. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 26(1), 1-12.

Krüger, M. (2018). Three-year-olds solved a mental rotation task above chance level, but no linear relation concerning reaction time and angular disparity presented itself. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 328248.

Otenen, E., & Kanero, J. (2022). Locating past and future: the influence of spatial ability on time representation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 44, No. 44).

Razzaque. J., et al. (2024). Addressing the Pathophysiology of Mental Rotation Task (MRT) Deficits in Parkinson’s Disease Using fMRI—Defining Benchmarks (P8-3.018). Neurology (Vol. 102., No.17).

Shepard, R. N., & Metzler, J. (1971). Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science, 171(3972), 701-703.

Suzuki, A., Shinozaki, J., Yazawa, S., Ueki, Y., Matsukawa, N., Shimohama, S., & Nagamine, T. (2018). Establishing a new screening system for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease with mental rotation tasks that evaluate visuospatial function. Journal of Alzheimer's disease, 61(4), 1653-1665.

Thérien, V. D., Degré-Pelletier, J., Barbeau, E. B., Samson, F., & Soulières, I. (2022). Differential neural correlates underlying mental rotation processes in two distinct cognitive profiles in autism. NeuroImage: Clinical, 36, 103221.

Titze, C., Heil, M., & Jansen, P. (2008). Gender differences in the Mental Rotations Test (MRT) are not due to task complexity. Journal of Individual Differences, 29(3), 130-133.

Vandenberg, S. G., & Kuse, A. R. (1978). Mental rotations, a group test of three-dimensional spatial visualization. Perceptual and motor skills, 47(2), 599-604.

Weigelt, M., & Memmert, D. (2021). The mental rotation ability of expert basketball players: Identifying on-court plays. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 92(1), 137-145.

Zell, E., Krizan, Z., & Teeter, S. R. (2015). Evaluating gender similarities and differences using metasynthesis. American psychologist, 70(1), 10.